The Greatest Goalkeepers of the World!

Harald Anton “Tony” Schumacher!

From the “Anpfiff” book:

In my favorite film, "Rocky," Sylvester Stallone hammers the colossus in the ring. He sweats like the stoker responsible for the fires of hell. He wants to win. Rocky—a man from the gutter—wants to conquer his opponent, his poverty, his fate.

"That's you. Not a boxer. A football Rocky.

A boy who wants to get out of trouble," was the first thing I realized when I saw the film.

My "slums" were in Düren, one of the worst-affected cities in Germany by the war. But children can play even in ruins. We lived in a "poor people's settlement," and our neighbors were the "antisocial" people.

I was able to follow the decline of entire families; many fathers were alcoholics, many mothers a mixture of slobs and scoundrels. Of course, there were others, but poverty was everywhere you looked. At home, there wasn't a single piece of meat in the pot. Our diet consisted mainly of potatoes and more potatoes. For good measure, a leaf of cabbage. Not very varied.

My sister and I shared a tiny room. Actually, a larger drawer. This time of cramped conditions also gave rise to the claustrophobia that still haunts me today. On the field, I can't stay in my goal cage. I try to get to the halfway line as often as possible.

My father worked in construction. He left home early at seven. He came back in the evening completely exhausted. He was silent. In winter, he stretched his tired legs toward the stove.

"Father" – for many years, that meant to me: a pair of legs in front of the fire. He wasn't a drunk. Thank God. He was a quiet, simple, decent man. He's still like that today. Without his calm, honest nature, I might have gone astray. Many of my friends were ruined by the example of their drunken fathers.

My mother had the greatest influence on me. I spent the whole day with her, watching her sew for other people. And she kept telling me: "Leave it, boy. Poverty is no shame. Stay honest and hardworking. You have nothing to be ashamed of."

There was little distraction at our playground other than a sandbox – enough space for soccer. Soccer became my outlet. Finally, space to romp around. Away from the poverty at home. I played striker. He'll prevail," said the coach of "Schwarz-Weiß Düren," my first soccer club. My mother thought I should become a member.

Fighters live more dangerous lives, even as children. "You run too much, Harald. You're completely exhausting yourself," my trainer scolded. "You need to manage your energy and strength better."

"Right," echoed Mother. "He always comes home completely exhausted. Drenched in sweat. He can't contain his ambition. Always racing at full throttle. He looks really rickety."

Both of them were worried about my health. And again, my mother decided: "Now you'll find a steady, quiet position. Why don't you go in goal? That was something for you." So I became a goalkeeper. Because that was a "quiet position"...

I was twelve at the time. Even in goal, I remained immensely ambitious. The Rocky syndrome? It was clear to me: "You're just poor. A high school diploma is out of the question. University even less so. But to those who are allowed to learn, I'll show them what I'm made of."

I was never envious. I just didn't understand why everyone should have their place in the sun or in the rain from birth. The privileged boys weren't to blame for their parents' wealth. Envy is nonsense. Looking forward makes sense. I had to fight hard for everything because I simply wasn't particularly talented.

But fighters ultimately fare better in life than the highly talented, naturally blessed. I'm now firmly convinced of this – with the necessary distance from things. An initial handicap has become a ladder to the top for many. Streisand, with her silver eyes, Clark Gable, who used to have a pitiful stutter, finally made it. With iron diligence and will, with hard work on himself.

For me, the will was there first. In the duel of "field player versus goalkeeper,"

I made a good impression right from the start. I had no fear of injury and didn't think about possible dangers.

Win. Be the best.

By the age of 15, I was already training four times a week: twice with the youth team and twice with the first team. I lived like a monk. Football left me no time for girls. I didn't own a moped, and I only knew discos from the outside. Football was the meaning of life. And there was a dream: my role models were the "star goalkeepers" of the 1950s – Toni Turek and Fritz Herkenrath.

Every Sunday, I was able to reap recognition and admiration with my parades. I gained pride and self-confidence for the entire week. I forgot the cramped conditions and poverty of my settlement.

"Did you see how Harald held ?" people seemed to whisper.

"He's Helga and Manfred's son. That boy will become something special." That was grist to the mill for my ambitious aspirations.

Social advancement through sport. That's how it was for me. I also saw the parallels to other social outsiders. Aren't most Olympic jumpers and sprinters Black? Like them, I too chased recognition. Even today, it's a mystery to me why not all Black people are world champions in something. In the early 1980s, we had a young Black player in our club in Cologne.

Toni Baffoe was 18 years old, played in the A-youth team, and wanted to become a professional. His performances were too inconsistent; he was easily discouraged and prone to self-doubt. This made me furious. "Listen," I shook him. "If I were Black, which for many means dirt, if I were at the bottom like you, then, damn it, my skin color would be reason enough to become the best footballer in the world." Don't let yourself get down like that, man. Show them what you're made of! Unfortunately, Baffoe didn't have enough grit and didn't – like me – have a severe allergy to humiliation.

Prom after dance class. I was sixteen. I had successfully overcome shyness and the tango step. The girls were nice – my fingernails were sparkling clean. I enjoyed the company of well-groomed peers, Coke and soda, and a few jealousy squabbles.

Finally, the eagerly awaited prom. The first social event. And the first clothing "drama." My communion suit hadn't fit long ago. I didn't have any cousins my own age from whom I could have borrowed a suit. All that remained was my father's good dark blue one.

"Out of the question," I protested to Mother. "Father's suit looks like a saddle on a pig. I want my own!" "And how much money are you going to pay for it?" Mother asked.

"You're a bit megalomaniacal."

" Gritting my teeth, I set off in Father's freshly ironed suit—with suspenders because the pants were much too wide. Among all my smartly dressed and well-dressed classmates, I felt like the village proletarian. I've rarely felt so miserable. I felt like a "white Negro"—and was determined to get rid of this skin as quickly as possible.

I put my full concentration into training. Through targeted progress, I wanted to make it into different national teams. And I did: Düren District – first level; Middle Rhine Selection – second level; West Germany – third level; Youth National Team – fourth level.

Everything went smoothly until the end of the 1960s.

The coach of the youth national team at the time was Herbert Widmayer; he had watched me at tournaments. The decisive moment came during a match for the West German youth team: at the end of the tournament – a penalty shootout. I saved three of five shots. After that, my name was suddenly on everyone's lips: "Schumacher, Schwarz-Weiß Düren, that boy is one to watch."

The clubs' and the DFB's (German Football Association) snoops were wide awake. My inclusion in the national youth team was only a matter of time. Most of the national youth players already had a contract with one of the Bundesliga clubs.

Jupp Röhrig, youth coach of FC Köln, then suggested I try out for the Cologne youth team one day. I was sixteen at the time and felt enormously flattered. But I had to – reluctantly – decline the offer.

"I have to get a job," my mother decided.

"Soccer —maybe later, but first you'll learn something proper."

No sooner said than done: I became a coppersmith – an incredibly physically demanding profession, by the way.

After my journeyman's exam, Röhrig knocked again.

The time had come. "I'll come. Mother agrees."

That was the new beginning of my life.

Football – nothing but football, in mind and body. Every day.

Heavenly!

I was a professional, but without today's pressure to perform, without the press, without rivals, without the pressure to be and remain number one. For the first time in my life, I was earning money, a lot of money: 1,200 DM a month – and that at 18. In my final year of apprenticeship, I had received 320 DM a month.

Now there was also an annual bonus of 30,000 DM. All in all, an annual income of over 45,000 DM. I thought it was fantastic. My father would never have been able to scrape together that much money, even if he had worked day and night.

I had already done quite well in the youth national team. I was almost a bit of a "star," or rather, a "starlet." "Schumacher, he's a great kid," I'd heard. But very soon it became clear that I had some weaknesses – and that meant I had to work hard on myself. I had already thought I was the greatest. But in reality, I was "Mr. Nobody."

The difference between amateur and professional football is like the difference between raspberry ice cream and a skyscraper. Huge. Just like the challenge for me.

The "number one" in Cologne was Gerhard Welz. A madman, a kind of Rocky. He trained like a maniac. Full of youthful self-confidence, I thought: "Schumacher, goalkeeper of the youth national team, just sweep him away!"

And I immediately realized it wasn't that easy. The strikers played like pure devils. Lightning fast. Blasting, precisely placed shots on goal, balls like Welz's saves, remained – still – out of my reach.

Difficult times followed. I played in unimportant games, but not a single Bundesliga or cup match. Purely vegetating. A half here, a friendly there – not the slightest chance of a breakthrough. Despite training and hard work, nothing was happening. I was treading water.

1974/1975, Stadium Radrennbahn Muengersdorf, 1. FC Cologne versus Borussia Moenchengladbach 1:2

Until the day Welz was injured: a ruptured kidney and a head injury.

The chance? My chance?

Think again.

I shared the number one title with Topalovic, a Yugoslavian.

1. FC Köln had two mediocre goalkeepers instead of one top-notch one...

But: The time of naive hopes, the time of illusions in the 29-year-old national youth team, those were just fond memories.

The first training session with Rolf Herings, the goalkeeping coach at 1. FC Köln, was the moment of truth. Balls were flying around my ears – I couldn't catch a single one.

Years later, Rolf confided in me: "You were completely crushed. There was no trace of self-confidence left. You were offended by every remark.

You hopped after balls like a squirrel and fell on your stomach like a ripe plum from a tree. But you wanted to learn. That impressed me. Your ability to persevere, even after hours of training, completely exhausted. You were always ready to use every last bit of your strength. 'Better that than slaving away as a coppersmith for eight hours,' you said, Harald. That impressed me."

Topping-out ceremony in Mechernich, near Cologne. Heinz Flohe had invited us. The national player and Cologne soccer star had built himself a house. Beautiful, large, and expensive. The builder was Rüdiger Schmelz, Flohe's manager and supervisor. Admiringly, I dreamed of one day achieving the same level of success as Flohe.

"Would Schmitz be a good fit for me, too?" I asked him, embarrassed. "Of course," he said. "You, need a manager to bring discipline and self-confidence into your life and your game." Schmitz was 31. I was 19, shy, and—still—quiet. A completely normal young guy from the provinces. I immediately trusted Rüdiger Schmitz. He, too, liked me, but he thought my strong attachment to my mother was exaggerated.

"Harald, you should keep a little more distance from Düren and your childhood," he recommended. "Otherwise, you'll never make it." He knew how much I loved my mother, and he thought that was fine in principle. It only bothered him that whenever I had the slightest doubt about the world or myself, I always sought refuge in her, and found it. Mother stood by me unconditionally. "It's poison," Rüdiger scolded, "that you always let your mother console you. Even when you've made the biggest mistakes. Mama's boys have no place in professional football."

I didn't know the answer, I was disturbed. "Directness, ambition, and even brutality are the virtues in demand," Schmitz continued. "You should finally put your umbilical cord away, otherwise you'll trip over it."

Rüdiger helpfully replaced my parents' home for me at first, but then he left me alone more and more often and pushed me, kindly but firmly, into a life where I was on my own. It was a hard road, paved with humiliation. And for a long time, I constantly felt overwhelmed.

I earned the not-so-glorious nickname "Fidgetty Philip" in goal between 1973 and 1977. Weisweiler, my coach from July 1976, didn't utter the slightest criticism in my presence. He simply ignored me, only to later ridicule me thoroughly in public.

Hennes Weisweiler is sadly dead. He was a very good coach and a terrible judge of character. Instead of helpful criticism, he spread caustic, unsettling ridicule.

At one point, he decided to "give me away" to another club. I was deeply hurt, offended, and insulted.

"Get rid of Schumacher!" Weisweiler yelled.

I found out about it indirectly. And finally, I wanted to leave, too. My appearances were sporadic, and I was ready to throw in the towel.

At that time, Rüdiger Schmitz had a house in the Eifel, right on the edge of the forest. We would walk for hours. "It calms the mind," smiled Rüdiger, "the fresh air drives the fog out of the hothead."

After a few steps, he stopped, suddenly quite serious: "You're a natural talent," he declared, almost solemnly. "You're like a diamond still hidden in a lump of ore.

How many times does it have to be polished until it's perfect? If you work energetically on yourself, if you polish away all your flaws and mistakes, you can release the preciousness within you."

This meant I was facing a new beginning. Rüdiger demanded extreme discipline. When he said, "Come at 6 p.m.", it meant 6 p.m. sharp, and not a minute earlier or later. "Focus exclusively on your coach and teammates," he insisted. "I don't think much of distractions right now."

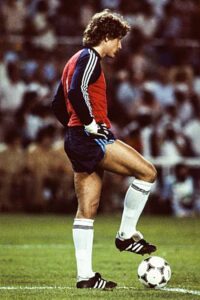

German goalkeeper Harald Schumacher.

Schumacher, the "happy Cologne character," became more serious, more thoughtful. But the "fidgety Philip" was far from over. All of Cologne continued to amuse himself with Topalovic and me. The two of us were the problem cases of our team, constant topics of discussion for the board and the club doctor's concern. Slowly but surely, I became a complete bundle of nerves.

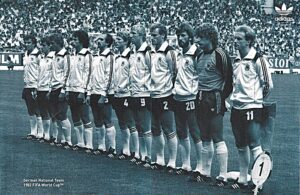

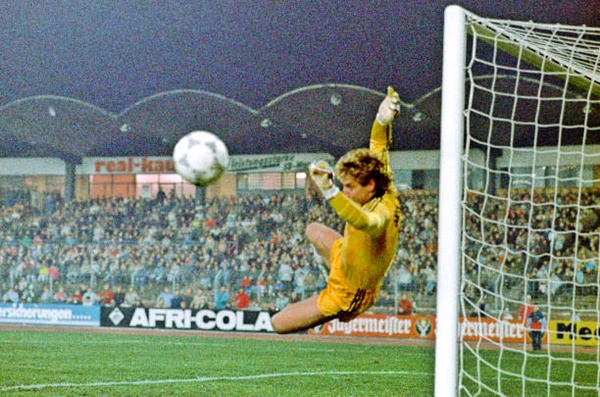

Bundesliga, 1982/1983, Stadium am Boek Elberg, Borussia Moenchengladbach versus 1. FC Cologne 1:4, scene of the match, keeper Harald Schumacher

"You want to do too well. You're overzealous," the club doctor, Dr. Bonnekoh, explained to me. "Don't be so hectic. Try to gain some distance, stay cool. Why don't you try to learn to control yourself, for example, through autogenic training."

That too. I reacted stubbornly. "That's out of the question. I don't believe in all that crap about horoscopes and that nonsense anyway." "Try it anyway. It can't hurt you. It's completely harmless." I realized that and trotted obediently to Dr. Schreckring, a very nice doctor.

"Think of something nice," she taught me.

"Vacation, beach, sea, sun, family vacation.

Your arms and legs become heavy.

The solar plexus radiates warmth.

You concentrate.

You play, want to catch every ball….

Like a tiger awaits its prey.

Let it come, grab it with lightning speed..."

At first, I practiced for about half an hour a day, then six times a full hour to really learn the technique. Since then, I've used it during training and before every important game.

Concentrate, switch off, a thousand times. True greatness is self-control.

Even at the 1986 World Cup in the cauldron of Monterrey before the penalty shootout against Mexico.

Franz Beckenbauer reported on it: "Toni is sitting on the grass, his hands pressed against his temples. I knew the game had absolutely drained him. Even though he's standing most of the time, he's losing three or four liters of sweat."

He's concentrating so hard that he's had cramps a few times. I go to him. No one can imagine the pressure Toni was under. I can only guess, having never had to go through anything like that as a player. If you fail now, the team will be eliminated. All hopes are on you. I went to him; somehow he seemed distracted.

'What is it, Toni?' I asked quietly.

He didn't hear me.

'What's wrong?' I asked again. Again, nothing.

Then, finally waking up again: 'Franz, be quiet.

What's wrong?' And then he yawned. It really was as if I had woken Schumacher from his sleep."

Franz had observed carefully. I was gone. I had recovered from the fight.

Delay hasty reactions, wait.

After that, I was able to save two penalties.

Penalties are torture... controlling reflexes, shooting out in the last hundredth of a second. A broadening of perception. Simply switch off thinking and considering.

During a penalty shootout, the goalkeeper is to the other players what the madman is to the normal person. He is the lightning catcher; like a magnet, he has to direct the approaching leather ball towards his body.

I owe it to Dr. Schreckling that I can channel my madness into very specific directions.

Back to 1977. The club manager at the time was Karl-Heinz Thielen, who then resigned from his position as deputy chairman of 1. FC Köln in October 1986.

He didn't think much of my autogenic training. Bluntly, as is his way, one day, five games before the end of the Bundesliga season, he gave me a good dressing down:

"Listen, Toni. We're looking for a new goalkeeper. We want to let you go. There's no point in this anymore. Weisweiler doesn't want to work with you anymore."

Training, concentration. Was it all for nothing? Didn't I make fewer and fewer mistakes the more often I played? My error rate had dropped from 30 to 27 percent. I had to try to remain error-free in these five remaining games. If possible, until the 1977 DFB Cup final. I had resigned myself; I didn't want to stay in Cologne anymore, but wanted to try to be as perfect as possible in order to at least secure favorable terms when changing clubs.

Norbert Nigbur has already been named as my successor. Frustration. Impatience. I won't get the chance to show my best side.

Topalovic, considered a bit more consistent than me, played all the Bundesliga games. I sat on the bench, in top shape.

The opportunity finally presented itself in the game against Hertha BSC. Topalovic, who suffered from severe fear of flying, decided not to travel to Berlin.

So I flew in his place – and made fantastic saves. No mistakes, brilliant saves. The result: 1-1 my achievement. I was the number one in Cologne. Finally.

1977 in Hanover: Final against Berlin. Norbert Nigbur was in goal for Hertha Berlin, but had already been in Cologne for negotiations. His contract with 1. FC Köln was 90 percent finalized.

We won 1-0. Nigbur raged, argued with the referee, and claimed that we Cologne players had bribed the referee. This meant that he was no longer an issue for the Cologne board members.

Two days later, we flew to Japan for a friendly match. On the plane, Weisweiler, who could only acknowledge successes, sat down next to me. "Listen, Toni," he growled. "I don't want to beat around the bush here. You have to know one thing. You're number one for me now."

I was indescribably happy. Things were looking up. But as Rüdiger Schmelz explained to me so dryly after a well-deserved break: I would only become the greatest, the best, if I continued to train at least 20 percent more than my rivals. "Because the real fight only begins when you're dead tired. Being knocked out and saying okay. That's the secret of success."

A lot had already been achieved in Cologne. Little Harald from Düren had become a great Toni. Toni, because my middle name is Anton. But above all, it was a reference to Toni Turek, the greatest German goalkeeper of the post-war period.

Toni. A first name became a title of nobility for me.

In 1977, 1. FC Köln won the DFB Cup, and in 1978, the Bundesliga and DFB Cup titles. In 1978, the World Cup took place in Argentina. Helmut Schön was the national coach, and Sepp Maier, my great role model, was in goal. I would have been happy to be there as number two or three. "Whatever Nigbur, Franke, and Burdenski catch, I'll catch," I said in a newspaper, offended at not being invited.

Young Schumacher alongside the great Sepp Maier

Brashness – that was frowned upon. Helmut Schön, a strict Saxon, liked it even less. "Schumacher? A loudmouth, an immature brat," was his verdict. In retrospect, I think the man was right. Maier was a superb goalkeeper, played 400 games without a break, reliable and consistent. Why should the national coach look for problems and invite me? Perhaps that would have irritated Sepp Maier?

In 1978, Jupp Derwall became Helmut Schön's successor, and initially behaved towards me like his predecessor. I was given one chance, for half a game: during an international match against Iceland. After that, for a year, “FDuien kPstriellses” promoted me: "Schumacher, outstandingly good, great saves, deserves his place in the national team."

1982 World Cup Finals, Second Phase, Group B, Madrid, Spain, 2nd July 1982, West Germany 2 v Spain 1.

Derwall was under pressure. Did he have to call me up for the national team?

Norbert Nigbur remained his favorite. Until that disastrous lunch: Nigbur was sitting at the table with his girlfriend, trying to get up after the lovely meal.

Impossible. The knee – immobile.

"Trapped meniscus," the doctors diagnosed.

The end of a career... the beginning of mine?

Franke or Schumacher? Another forced decision for Derwall before an international match in Munich, this time against England.

"I want to play the match, for 90 minutes," I announced in an interview. "Insolence, blackmail, outrageous impudence, " the national coach ranted, beside himself with indignation – before finally giving in.

The 1980 European Championship in Rome was a highlight. I was able to fight and win with the best team I could imagine. With young talents: Bernd Schuster, Hansi Müller, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge.

No big stars like 39 Overath, Beckenbauer, Netzer.

The atmosphere was excellent, the team spirit ideal. Freshness and enthusiasm. Derwall rarely had to intervene.

We became European champions. That was almost a given.

From then on, I was the undisputed number one in goal. With all the consequences: pressure to perform, the certainty that numbers two and three were waiting for me to pinch my meniscus, break my leg, or something else. Bad luck can't be ruled out. God has that in His hands. I can't defend myself against it. Success is like beauty; it can't last forever.

Excerpted from the book: "Anpfiff" (1987) autobiography of German goalkeeper Harald "Tony" Schumacher! (Pages 20-39)

FOTOGALLERY

Harald Schumacher of West Germany during the European Championship match between West Germany and Portugal at Meinau, Strasbourg, Paris on 14th June 1984

02.03.1985 - Portugal / Republique Federale Allemagne - Eliminatoires Coupe du Monde 1986,

Diego Maradona et Harald Schumacher ont reçu un soulier d'or à Paris le 13 novembre 1986, France.

Harald "Toni" Schumacher (left) and German team captain and goal getter Karl-Heinz Rummenigge hug each other after the final whistle of the World Cup final on 29 June 1986 at the Aztec Stadium in Mexico City,

Schalke TW Harald Schumacher. Saison 1987-1988 Hannover 96 (Rot) gegen Schalke 04 3:1.

Saison 1981/82 Eintracht Braunschweig gegen den 1. FC Köln 4:4.

Deutschland gegen Spanien 2:2 im Niedersachsenstadion in Hannover.

Saison 1981/82 Eintracht Braunscheweig gegen den 1. FC Koeln 4:4 .

08.07.1982 im Sanchez-Pizjuan-Stadion von Sevilla im Weltmeisterschafts-Halbfinalspiel gegen Frankreich in der Verlängerung den 3:3

16.11.1983 vor 62.000 Zuschauern im Hamburger Volksparkstadion das EM-Qualifikationsspiel gegen Nordirland mit 0:1.

Harald Schumacher of West Germany during the 1982 FIFA World Cup Semi Final match between West Germany and France, at Ramon Sanchez Pizjuan, Sevilla, Spain on 8 July 1982

Harald Schumacher of West Germany during the International Friendly match between West Germany and France at AWD Arena, Hannover, Germany on November 19th, 1980

© Translated from German to English by:

Eni F. Kapurani (original fan of Germany and especially of Tony Schumacher)

June 27, 2025

_____________________

Sports Vision +Plus / Champions Hour in activity since 2013

Some of photos are collected from google search. If you have any issue on photos, please let us know first before you are making any reports!

No comments:

Post a Comment